(Samaj Weekly)

– Abhay Kumar

While covering the encounter of the gangster Vikas Dubey by Uttar Pradesh (UP) police, the mainstream Indian media – particularly Hindi newspapers – appears to have condoned the extra-judicial killing. They have again failed to act as a defender of civil rights.

The diseased, Dubey’s, criminal life spanned 30 years. He has been accused of 62 criminal cases. The criminal charges against him include five cases of murder and eight cases of attempt to murder (8). Earlier, he has also been booked under the draconian UP Gangsters’ Act, Goonda Act, and the National Security Act. In 2001, he was accused of killing a state minister within a police station. A few days back he was arrested by Ujjain police (Madhya Pradesh) for killing eight policemen. Eventually, he was being brought to Kanpur by the U.P. police. Dubey was killed in a police encounter on the early Friday morning on his way from Ujjain to Kanpur.

The encounter of Vikash Dubey became the front-page story in most of the newspapers. Some newspapers wrote editorial on this incident. For example, Hindi daily Haribhoomi calls the encounter as “justice” given “on the spot”. Its front-page headline (New Delhi, July 11) reads “Justice onspot”.

Similarly, Dainik Bhaskar (New Delhi, July 11) portrays the encounter as “justice” (Encounter wala insaf). Another Hindi daily Rashtriya Sahara, too, appears to have upheld extra-judicial killing by the police. In its front-page headline, the Hindi daily writes “The end of Vikash Dubey comes instantly” (Vikash Dubey ka ant…turant). Dainik Jagran (National July 11) expresses the same spirit in its front-page headline: “Gangster Vikash Dubey killed in an encounter” (Muthbhed men gangster Vikas Debey ka kam tamam).

Can an encounter by the police, in any condition, be justified in a democracy? Who will deny that the job of the police is to investigate and produce an accused before a court? In a landmark judgment in 2012, the Supreme Court warned against the practice of encounter: “It is not the duty of the police officers to kill the accused merely because he is a dreaded criminal. Undoubtedly, the police have to arrest the accused and put them up for trial. This Court has repeatedly admonished trigger happy police personnel, who liquidate criminals and project the incident as an encounter. Such killings must be deprecated. They are not recognised as legal by our criminal justice administration system. They amount to State sponsored terrorism.”

Contrary to this, Hindi dailies seem to have condoned the encounters. They appear to have justified the extra-judicial killing. They seem to have favoured bypassing proper legal procedures, upholding “instant justice”. It is unfortunate for a democracy that a considerable section of media does not seem agitated against the practice of meting out justice as a kangaroo court does. Sadly, the above-mentioned newspapers do not make much effort to go beyond the police version. They have presented the chronology of events in such a way to make the readers believe that the police had no option but to kill the “gangster”.

For example, the narrative, peddled by Dainik Jagran (National), seems to be based on the notes taken from the police. As the newspaper writes, Vikash Dubey, accused of killing eight policemen, was being brought from Ujjain to Kanpur by the police. When the police vehicle overturned near Kanhaiya Lal Hospital in Sachendi (Kanpur), the police jawans got unconscious for a while. Meanwhile, Vikash Dubey snatched a pistol from a police inspector and tied to run away. When the police started chasing him, he fired at policemen. In retaliation, the police forces and members of the Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS) killed him. Two jawans of the ATS also sustained injuries.

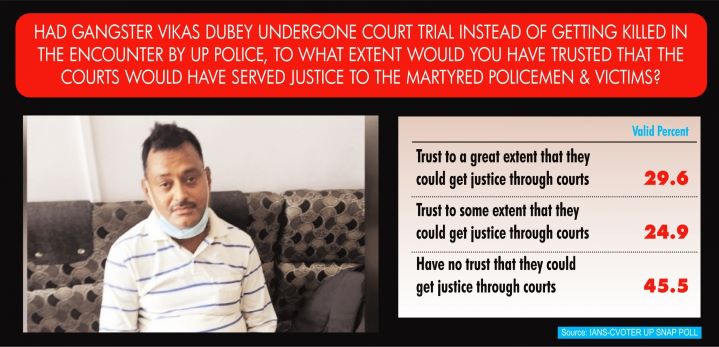

Such a narrative raises more questions than it answers. For example, when the police vehicle overturned, how could all the police jawans fell unconscious but Vikash Dubey did not? Was the security arrangement by the U.P. police appropriate, given the “dreaded criminal history” of Dubey? Is there any political pressure to silence him forever that outweighed the considerations of justice?

Instead of raising such questions, the tone of editorials, penned by several Hindi newspapers, has sounded apologist for the encounter. Rashtriya Sahara’s editorial (July 11) seems to be scolding those who have spoken against encounters. “But those who have condemned the role of the police and spoken loudly in favour of the judicial system, should know this fact that the accused of sixty serious cases has been enjoying impunity with the help of the same judicial system”. Rashtriya Sahara forgets to note that the police system is part of the judicial system.

The editorial of Dainik Jagran (National, July 11) says the same thing but says it indirectly. To justify the police action, the newspaper spends considerable energy on showing the loopholes of the judicial system. It argues that the judicial system of the country has been unable to punish the “dreaded” criminals. It even justifies the December 2019 Hyderabad police encounter of the alleged rapists. By such an act, it prepares the ground for the justification of the encounter. In our judicial system, the editorial argues, the pronouncement of sentences to criminals as well as the execution of the punishment is delayed.

Even if the editorial is justified in highlighting the limitation of the judiciary, it cannot be a ground for encounters. The primary job of the police, undoubtedly, is investigation. The police should collect evidence and put it before the court to decide. The Indian Constitution, similarly, talks about the separation of power. It opposes one authority encroaching upon the rights of other institutions. The principles of democracy are the rule of law and checks and balances.

However, the editorial of Haribhoomi does raise a few questions about the encounter. It is hopeful that the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) would take “serious action” since the matter has been brought to its notice. Haribhoomi’s editorial says that even “anti-national” Ajmal Kasab and Afzal Guru were brought before the court. Punjab Kesari (July 11), in its editorial, has hinted at the political angle of the encounter with the following words: “With Vikas Dubey encounter by the police, several secrets (rahasya) got buried too”.

The editorial of The Indian Express (July 11) is vocal against the practice of encounter. It has criticized Yogi Adityanath Government too: “There is, also, a thriving “encounter culture” and police impunity in UP. It is sanctioned by the ruling regime and shored up by the apparent lack of popular outrage at extra-judicial killings, if not outright popular support for such summary executions, and impatience with fundamental principles of criminal justice. Indeed, in a country governed by the rule of law, the UP Police has much to explain. But if it resists and refuses — as police forces in these situations do — the court must step in”.

Urdu dailies, unlike most of Hindi dailies, raise several questions about the encounter. Inquilab (Mumbai, July 11), in its lead story, says “After dramatic arrest, suspicious encounter, several questions raised, inquiry demanded”. Siasat (Hyderabad, July 11), has the following headline: “The dramatic killing of the gangsters in UP, Vikash Dubey falls a new prey to ‘encounter’ state” (“‘Encounter state’ men Vikas Dubey naya shikar, U.P. men gangster ki dramai halakat”).

Note that several cases of encounters by the UP police have been reported in the recent past. According to a report of The Indian Express, “Dubey is the 119th accused to have been killed in what police called cross-firing since the Yogi Adityanath government took charge in March 2017”. Another story in The Wire claims that “in the last ten months, UP police has conducted four police encounters per day”. This all points to the prevalence of gross violation of the human rights in UP.

It is disappointing that several Hindi dailies, while reporting the encounter, have not pressed the demand for the police reforms (police sudhar). However, two retired senior police officers, writing opinion pieces, have expressed serious concerns over the criminalization of the politics and politicization of the police.

Writing a piece in Amar Ujala (New Delhi, July 11) titled “Crime, politics, and police” (Apradh, rajneeti aur police), Prakash Singh, former DGP, argues that the police should be kept immune from the political pressure. He rues that the erring officers, particularly those placed at higher level, go scot-free. He also tries to link the encounter with the problem of criminalization of politics. He cites the example of U.P. assembly (2017), saying that 36% of total MLAs has been charged with criminal cases. “If a large number of politicians with criminal backgrounds would enter the assembly, how will then the organized criminal gangs be checked?”, the former DIG Prakash Singh has asked.

Julio Ribeiro, former DGP of Gujarat and Punjab, has stressed the issue of “politicization of the police force” in his opinion piece in The Indian Express (July 11). In his article, he contends that the process of “political meddling” and “patronage afforded to corrupt officials” began in the 1980s. In this way, he tries to show a contrast between the period before the 1980s and after the 1980s. Showing a link between Friday’s encounter and the regime of Yogi Adityanath, Julio Ribeiro says that UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath “openly boasted of controlling crime by the encounter method”. In the end, Ribeiro concludes that by resorting to “shortcut”, such as encounter”, the UP chief minister is “ensuring the rise of enterprising policemen, who have become law breakers instead of law keepers”.

While Prakash Singh and Julio Ribeiro are correct to raise the issue of criminalization of politics and politicization of the police, the issue of police reforms cannot bypass the question of lack of diversity in the police department. The Indian police came into existence with the Police Act, 1861 during the British colonial rule. Before the Independence the Muslim representations in UP was not as bad as it is seen today. For example, the shares of Muslims in the police department were 50% cent (1921), 48% (1935-36), and 40% (1947). Unfortunately, the discriminatory policies of “secular” governments in post-Independence made Muslim representation in police fall drastically. The latest figure (2012) suggests that Muslim representation in the police is a mere 6.5%, half of their population. Similarly, the representation of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in the police at an-all India level is also inadequate, i.e. 16.5%, while their population is 27%. The proper representation of Muslims, as well as other deprived communities, would make the police department more inclusive and less prejudiced against the weaker sections.

(Abhay Kumar is a Ph.D. from JNU. He is broadly interested in Minority and Social Justice. Earlier, he held a Post-Graduate Diploma in English Journalism from Indian Institute of Mass Communication, New Delhi and worked as a Delhi-based reporter with The Indian Express. You may write to him at [email protected]).