New Delhi, (Samajweekly) The downfall of the administrative and political set up in Kashmir in the late 1980s and early 1990s had a direct bearing on the rise of militancy, which was fully aided and abetted by Pakistan and took a totally communal colour.

Veteran journalist Brij Bhardwaj, who covered Kashmir for over 50 years and is a witness to one of the tumultuous chapters of the state’s and nation’s history, says: “The continued political bungling by the Centre and state governments gave the space to those elements who always wanted to whip an anti-India wave in Kashmir. In the 1950s and 1960s and a big part of the 1970s, there was a leadership which could take decisions and largely kept the separatist and pro-Pakistan elements in check.”

Official patronage of militancy

In the late 1980s when Farooq Abdullah was the Chief Minister in Jammu and Kashmir, and Mufti Mohd Sayeed the Union Home Minister, thousands of people were going to Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK) for training.

“Buses were running to LoC, hundreds were crossing over and coming back after getting training. Didn’t the Chief Minister know this or what was the Army or BSF doing at the LoC? They are all guilty. That is why I say there was official patronage. Being in Kashmir, and talking to all, whether the locals or leaders or the security officers, I could assess that the system was rotting … and they were all in it. All those big central officers posted in Kashmir that time made huge fortunes.

“So when there is official backing, nothing can prevent the situation from going downhill. And that is what happened in Kashmir. First it was the JKLF, then many other groups cropped up. There was no stopping them and they went full throttle. They resorted to targeted killings of Kashmiri Pandits and attacked those Muslims who were perceived to be pro-India.

“The Kashmiri Pandit community was seen as pro-India. So to make them fall in line, targeted killings were done and an atmosphere of fear was created for them to either join the militant movement or leave or get killed. JKLF had the total support in our Kashmir as well as in PoK But other groups didn’t have,” Bhardwaj told IANS.

The veteran journalist says the kidnapping of Rubaiya Sayeed on December 9, 1989, was a real one. “Mufti was the Home Minister and there were inputs that his son would be kidnapped, but no one could have thought the daughter, a girl, would be kidnapped. Farooq Abdullah was against releasing the terrorists, but then they were set free.”

No Control

Anti-India elements have always been in Kashmir, but it was the leadership that knew how to control them. In 1947 and 1965, infiltration happened, Pakistani militants entered homes in the valley but the locals did not support them. The locals gave them away, thus blowing up the Pakistan agenda.

In 1965, it was the Gujjars who first gave the information about the infiltrators. “A Gujjar who gave the information to an Army officer was slapped by him, saying ‘what you think we are fooling around?’ and, then when firing happened in Batmaloo (Srinagar), all hell broke loose. In 1971, the India-Pakistan war happened, but there was no trouble within Kashmir.

“In the 1980’s this was not so. All had changed because there was no leadership to control the situation. The Rajiv-Farooq accord was there, but there was no trust. There was no political strength, no state administration and the Centre was weak. So things went out of hand,” says Bhardwaj.

“Without people like Late P.N. Haksar (former Principal Secretary to then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi) in Delhi, Late D.P. Dhar (former Advisor to Indira Gandhi) and old Kashmir hands like Late Vishnu Sahay (Secretary for Kashmir Affairs in the Ministry of External Affairs and later Union cabinet Secretary in 1958-1960 and 1961-1962), and late Bhagwan Sahai (Jammu and Kashmir Governor May 15, 1966- July 3, 1967), the Centre was clueless about handling the Kashmir issue.

“Then B.K. Nehru in April, 1984 was suddenly recalled after differences arose with Indira Gandhi over the dismissal of the Farooq Abdullah government, and the appointment of G.M. Shah, who led a faction of the NC, as the Chief Minister with support from the Congress without the floor test. Nehru was ousted and Jagmohan was brought in. Farooq Abdullah was miffed. Though he was friends with Rajiv Gandhi, who became the Prime Minister after Indira Gandhi was assassinated, the relations were not smooth. Farooq was dismissed as CM and later brought again and removed again. This political mistrust cost the state and the country a lot. The state had gone weak.”

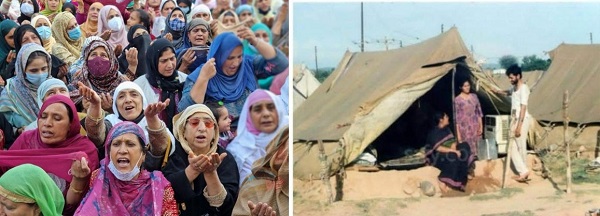

The Exodus

“By 1989, everything was like haywire in the valley. There was no administration. People were getting killed, kidnappings were happening, many Pandit women were abducts, brutally gang-raped and killed, firings ad cross-firings were happening almost every day… The militants had automatic guns, latest pistols. They were fully armed. Thousands of people would gather on the roads chanting ‘azadi’ and other slogans. Over 70 hardcore terrorists were released. Finally Farooq, before he could be sacked, resigned on January 18, 1990 and later left the country. Jagmohan had taken the charge a second time a day later in Jammu (January 19, 1990- May 26, 1990).

“What happened on January 19, 1990, was unprecedented. The Kashmiri Pandits were targeted and many of the community leaders, professionals and young men and women were brutally killed. This was not an all of a sudden event. There had been a systematic brainwashing of the locals towards the minorities. The Kashmiri Pandits were the most educated community in the state. They had the maximum number of central and state government jobs. So there was a kind of animosity against them. This suited those who were championing the separatist agenda,” says Bhardwaj.

He, however, said that Jagmohan could have prevented the fleeing of the minorities, if he had taken the decision of getting the police into strong action and the army on the roads immediately.

“If the political leadership was strong, this could have been prevented. But the right people were not there at the helm. A whole lot of non Kashmiri Maulvis had been touring the valley and inciting the youth to join the ‘jihad’. All these were from different parts of the country. There were intelligence reports. Why were these people allowed to move freely and incite communal passions?

“I was in Kashmir in the mid 1990s on a tour. I was staying in a houseboat in Nagin Lake. The owner told me that a non-Kashmiri Maulvi had asked a group of young boys, including his son, to go to Pakistan. The house boat owner, instead of reprimanding his son which could have proven counter-productive, asked his son to ask the Maulvi to accompany them. But when the boy asked the same to the Maulvi, he detracted and left after a few days. ‘I could convince my son and he saw the reason’, the house boat owner told me. So, not all Kashmiri Muslims were supporting the so-called ‘jihad’. What was needed was strong leadership to control the grave situation and stop the youth from falling down the precipice.

“For politics, power and greed, Kashmir has been destroyed. Its people have been wrecked. Each Kashmiri has lost someone and the Pandits cannot go back. They have lost their homes and they are suffering because of a weak governance.

“Kashmir is a tragedy where there are no heroes, but everyone has been a villain,” signs off the doyen, who saw Kashmir as a child in 1953, as a college student in 1956, as a journalist in 1971 and then as an expert.