This correspondence between a forgotten Indian and a famous American makes for moving reading. Sending such a letter showed exceptional bravery; but then MK Achutan had showed courage all his life, in overcoming his disadvantaged family background to study engineering, in combating the upper-caste prejudice he must surely have faced in school, college, and the workplace

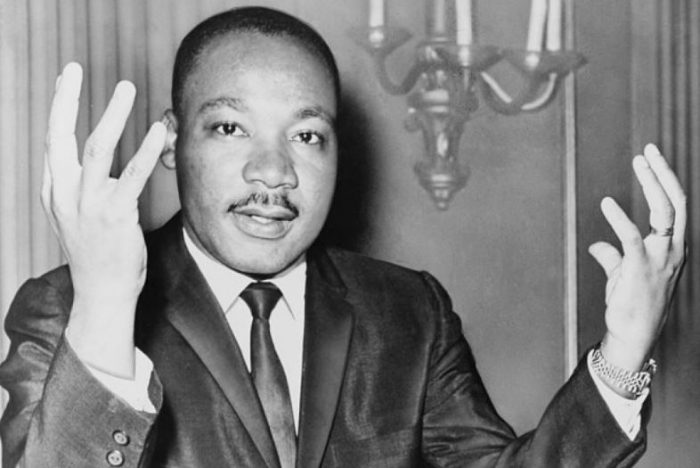

In February 1959, Martin Luther King and his wife Coretta arrived in India on a three-week visit. The American civil rights leader’s pilgrimage to the land of Gandhi has been extensively written about. However, while working on the papers of King at Boston University, I found a fascinating footnote that deserves rehabilitation.

Among those who read about King and his travels through India was a person named MK Achutan. Originally from Tamil Nadu, he was then working as a technical assistant in the Calcutta station of All India Radio. On April 28, 1959, he posted a letter to King at his home in Montgomery, Alabama. Achutan said he was 28-years-old, and a graduate in telecommmunications engineering from Madras University. He told King that he was “very much ambitious of coming to America for some further studies or training and I have been mustering all my efforts towards realizing this ambition”. He had written to several US universities with no luck so far, hence this direct appeal to King.

Achutan then provided King more details about his personal background. He was, he wrote, “in many respects, in a very disadvantageous position as I am born in a financially poor family belonging to a low caste, … [in] one of the most backward communities in India”.

“Education above primary classes,” continued Achutan, “is something very rare in my community and the very reason for my studying up to the Bachelor of Engineering degree was that I had high academic records and was awarded scholarship to meet tuition and maintenance by the Harijan Welfare Department of the Madras State Government and I got admission in Engineering College by virtue of reservation for backward classes in educational institutions introduced by the National Government after Independence … .”

There was reservation for Dalits studying within India, but not, alas, for those who wished to study further, outside India. Thus, as Achutan pointed out: “though [the] Indian Government is sending some people abroad every year for studies, no special consideration is being given to Backward Classes in selection and these Scholarships generally go to people of high social and financial status”.

Achutan had written to a number of American universities asking for information, and for forms for scholarships and assistantships, but had “received very curt replies or no replies at all from them”. He significantly noted: “At the same time, [high-caste Indian] persons who are already in America are easily able to take their relatives and closely associated friends with them to America and obtain financial assistances for them‘, as well as help them in getting forms, etc.

Achutan’s observations were absolutely accurate. The Indians sent abroad to study on government funds were almost all upper caste; and it was also upper castes who had the cultural capital and family connections to go abroad to study in a private capacity. Doubly burdened by his background, he was now asking King to help, by writing to universities and asking them to send him the necessary forms.

Achutan ended his letter to King as follows: “This is the first time I am writing a personal letter to America and my belief, due to obvious reasons, that you will have a sympathetic attitude towards me has prompted me to write to you… . I shall be thankful for an early reply from you.

Requesting you once again to excuse me for troubling you with this letter.”

Posted from Calcutta on April 28, 1959, the letter must have reached Montgomery in early May. However, King’s reply (a copy of which is in the Boston University archives) was posted only two months later, on July 14. He apologised for the slowness of his response, which was on account, he said, of “absence from the city and the accumulation of a flood of mail”.

“I have read your letter with a great deal of concern”, wrote King to Achutan: “Your problem is a real one and I hope it can be solved. You are to be admired for your determination and sense of direction”.

King told Achutan that he was not in the academic field and “not directly involved in any university work”. Yet he was moved enough by the request “to take your problem with some of the college presidents that I know personally. It seems to be that since you are interested in engineering, Howard University, D C, is the school which would best meet your needs”. King said he would write to the dean there, and as soon as he heard back, inform the Indian.

King’s own letter ended as follows: “Again, let me say how much I admire you for your positive drive and willingness to sacrifice in order to achieve. I hope for you a most rewarding future”.

This correspondence between a forgotten Indian and a famous American makes for moving reading. Sending such a letter showed exceptional bravery; but then M K Achutan had showed courage all his life, in overcoming his disadvantaged family background to study engineering, in combating the upper caste prejudice he must surely have faced in school, college, and the workplace. At the same time, Dr King’s reply is also graceful and generous.

It is an exchange that brings credit to both men. But what happened to the one who was unknown? King‘s doings from 1959 until his death in 1968 have been documented in minute detail. However, I was unable to find out what MK Achutan did thereafter. One hopes that he had the sort of “rewarding future” that his courage and his intelligence deserved.

Courtesy: By Ramachandra Guha / Navhind Times