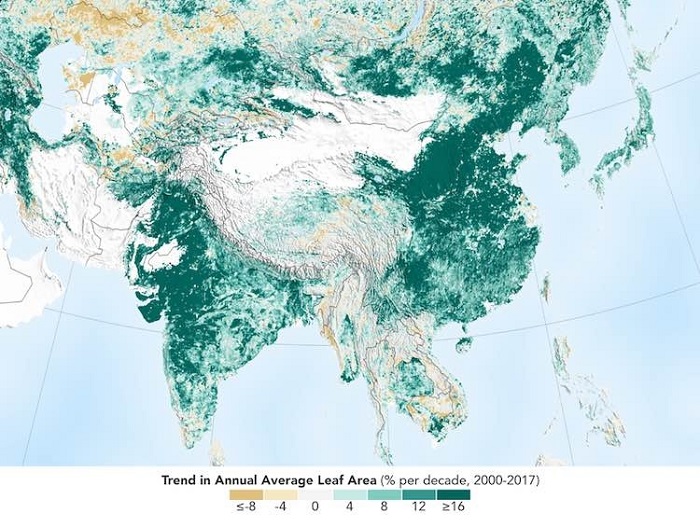

Washington, India and China are leading the way in greening lands, thanks to ambitious tree-planting programs and intensive agriculture in both countries, NASA satellite data has shown.

The world is getting literally greener than it was 20 years ago, the study published in the latest edition in Nature Sustainability on Monday said.

It showed that at least 25 per cent of the global foliage expansion since the early 2000s came from China, with India close behind.

This surprising new development detected by NASA satellites showed that the two nations with the world’s biggest populations were leading the way with their ambitious tree planting programs and intensive agriculture.

In 2017 alone, India broke its own world record for the most trees planted after volunteers gathered to plant 66 million saplings in just 12 hours.

The greening phenomenon was first detected in the mid-1990s, but they did not know whether human activity was one of its chief, direct causes, said researchers from the Boston University, who found that the greenery increase in the new century has been by five per cent — an area equivalent to the entire Amazon rainforest.

Rama Nemani, a research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and a co-author of the study said: “When the greening of the Earth was first observed, we thought it was due to a warmer, wetter climate and fertilization from the added carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.”

But with data from NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, scientists realised that humans are also contributing. “Humans are incredibly resilient. That’s what we see in the satellite data,” said Nemani.

“China and India account for one-third of the greening, but contain only nine per cent of the planet’s land area,” said lead author Chen Chi of Boston University.

“That is a surprising finding, considering the general notion of land degradation in populous countries from over-exploitation,” said Chen.

The new insight was made possible by a nearly 20-year-long data record from a NASA instrument orbiting the Earth on two satellites. It’s called the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, or MODIS.

The high-resolution MODIS data provides very accurate information, helping researchers work out details of what’s happening with Earth’s vegetation, down to the level of 500 metres on the ground.

The land area used to grow crops in the two nations have greatly increased both their annual total green leaf area and their food production.

The researchers found that through multiple cropping practices, where a field is replanted to produce another harvest several times a year — production of grains, vegetables, fruits and more have increased by about 35-40 per cent since 2000 to feed their large populations.

How the greening trend may change in the future depends on numerous factors, both on a global scale and at the human level in these countries.

Nemani explained that icreased food production in India is facilitated by groundwater irrigation so in case groundwater is depleted, the trend may change.

“But, now that we know direct human influence is a key driver of the greening Earth, we need to factor this into our climate models,” Nemani said.

“This will help scientists make better predictions about the behaviour of different Earth systems, which will help countries make better decisions about how and when to take action.”

The researchers, however, also pointed out that the gain in greenness does not offset the damage from loss of natural vegetation in tropical regions, such as Brazil and Indonesia.

The consequences for sustainability and biodiversity in those ecosystems remain, but overall, Nemani sees a positive message in the new findings.