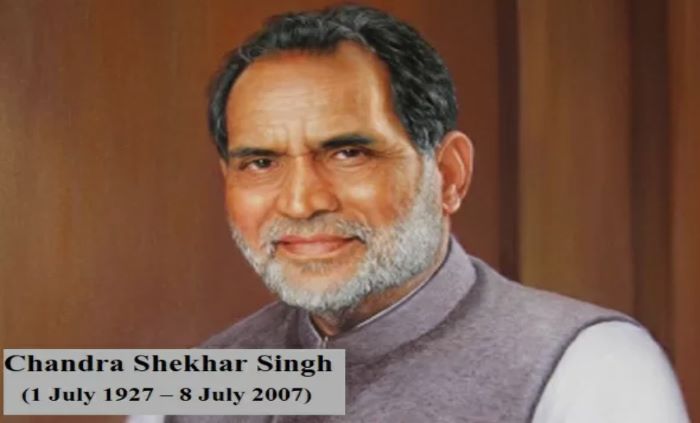

Chandra Shekhar’s unforgettable resistance to globalisation

Prem Singh

Prem Singh

(SAMAJ WEEKLY)- (I wrote this Tribute to Chandra Shekhar on his demise on 8 July 2007. It was published in the Mainstream Weekly, and further compiled in the book published by the Parliamentary Secretariat on him. The same is released again on his death anniversary for new readers.)

I was not close to Chandra Shekhar and was not quite sure that he would even know me as a socialist activist and writer. But once a friend told me that Chandra Shekhar would like me to meet him some time. I was told that he wished to discuss his approach to the problem of corruption about which I was very critical in my writings. But I could not meet him then and he became the Prime Minister of India. I found the opportunity of meeting him personally after his brief spell as PM was over. I remember visiting him three times with my senior socialist friends Vinod Prasad Singh, Brij Mohan Toofan and Raj Kumar Jain. On one occasion I saw him alone with a friend who had some problem with his academic career. Chandra Shekhar promptly responded by trying to help. Each time that I met Chandra Shekhar I found him to be a warm and concerned person, ever ready to listen and help. I know several occasions when he helped needy patients in their treatment, particularly in the Government hospitals.

He knew that I was critical of some of his ideas and actions in my writings and speeches, yet I did not find any reservations or hostility on his part whenever I met him. I mentioned this to my journalist friend Hari Mohan Mishra, who happened to be from Chandra Shekhar’s constituency and not an admirer of his political decisions as such. He observed that these are the factors in his character which made him a bada adami.

The socialists of younger generation may not agree with his political moves but they do admire him for his ideological clarity and political courage which is increasingly missing from the Indian political arena. Even if one were to keep aside the adage of ‘former Prime Minister’ for Chandra Shekhar, there are many other points of recognition that establish him as an exceptional leader of men and a real human being. In fact his stature among contemporary leaders could have been better had he not become the country’s Prime Minister for four months.

Chandra Shekhar’s political thought and concern found genesis in the socialist movement and ideology. Gandhi had been a deep influence on his ideas and personality. Chandra Shekhar was an erudite leader. He edited an important journal of socialist movement ‘Sangharsh’ which was initially brought out by his political guru Acharya Narendra Deva. Chandra Shekhar edited another journal ‘Young Indian’ in Hindi as well as in English. In the 19 months of his imprisonment during the Emergency he wrote a diary, published in two parts under the title Meri Jail Diary. His autobiography Zindagi Ka Karvan and several other books that contain his ideas and interviews have been published by Rajkamal Prakashan, Delhi.

Chandra Shekhar enjoyed close relationships with writers and journalists. He was not and never claimed to be a theorist of socialism like JP, Lohia and Acharya Narendra Deva. He, on the other hand, was a practical politician within the parameters of socialist ideology. In his own way he was a thinker who expressed his ideas as a writer, as an editor and as a leader during the long span of his political career. The consistency of his ideas was remarkable and his concerns were always directed in the interest of the downtrodden. Due to his defiant and rebellious temperament, he earned the name of Young Turk.

Chandra Shekhar is with us no more. History alone decides the relative significance of a leader who should be remembered, and how. The assessment of such significance cannot be established without deep cognition. In statements and comments of leaders and journalists published in the newspapers the day after his demise, he was remembered as a socialist stalwart, parliamentarian, secularist and a friend for his qualities of fearlessness, straight-forwardness and generosity. However, in most of these glowing tributes except in Janeshwar Mishra’s passing comment in ‘Dainik Bhaskar’ – ‘Chandra Shekhar was opposed to the slaving-after for foreign capital’- there was hardly any mention of the Chandra Shekhar who had launched a staunch and sustained opposition to globalization, which arrived in the guise of new economic policies and came to be known as liberalism and later as neo-liberalism.

If one fails to remember this unique political stance, then Chandra Shekhar is no different from yet another ‘good’ leader. But the truth is that in mainstream politics, apart from some Leftist leaders, he happened to be the lone leader who, in Parliament and outside, was vociferous and vocal against globalisation that has arrived in the guise of the New Economic Policies. The point where Chandra Shekhar moved ahead of the Leftists was that he did not stop at a critique of globalisation but went on to offer a possible answer.

Chandra Shekhar believed in the Gandhian economic philosophy as an alternative to the new economic policies. He wrote: “The call for Swadeshi and Swavlamban given by Mahatma Gandhi was not merely a slogan. It was an economic philosophy of life aimed at self-development.” In his short span as the Prime Minister, Chandra Shekhar firmly resisted the dictates of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. When the Vice President of the World Bank came to India during his tenure, Chandra Shekhar’s clear observation was: “The market economy run by you is confined to a very small population. Please do remember, they alone do not constitute the entire nation.”

As the first phase of liberalization in India drew to its completion, Chandra Shekhar, on 9 August 2000, the 58th anniversary of the Quit India Movement, launched the Vikalp Abhiyan — a protest march against the forces of globalization. On this occasion he observed: “Our country, forgetting the vision and dream of Swaraj, was once again falling into the shackles of economic slavery which would place its political and social freedom at risk in the hands of the international market. The time had arrived to do or die in order to resist neo-imperialism, entering the country through the market.”

Chandra Shekhar organized a public awareness campaign — Jan Chetna Abhiyan — against the Dunkel Proposals. He participated in Swadeshi Jagran Manch on the call of the RSS Chief Balasaheb Deoras. However, he became disillusioned with that very soon. In the year 2000 on the occasion of August Revolution Day he launched the Vikalp Abhiyan, mentioned above, to protest against the second phase of globalization. But as he confessed, the hope of a powerful movement emerging out of this Abhiyan could not be achieved. Consequently he planned a Yatra from Puri in Odisha to Porbander in Gujarat. An effort was also made in this direction with the support of four former Prime Ministers viz. V.P. Singh, P.V. Narasimha Rao, H.D. Deve Gowda and Inder Kumar Gujral.

It becomes evident from these concrete ventures and programs that his protest against globalization was not merely verbal. He was of the firm belief that the larger poor population of India will bear the brunt, not benefit, from globalization. Not for a moment did he believe that there could be a ‘human face’ to such a system. Yet the fact remains that he could not achieve much success in spearheading a strong movement against globalization. A point to consider here is that Chandra Shekhar did not have much of a link with the movements and activists outside mainstream politics, who had been offering a relentless fight through their own small but substantial thoughts programs. Had this happened the picture of the politics might have been much more different. Till the end he held the view that politics as such should not be discarded for being bereft of any positive potential to face the challenges of globalization.

Chandra Shekhar continued to search for an alternative to globalization within the mainstream politics. The need, however, was to look beyond the considerations of the ‘mainstream’ in order to circumvent the compromises and pitfalls inherent in mainstream politics. Who could have understood this need better than Chandra Shekhar? In his autobiography he wrote, “There were five issues involved in Bharat Yatra — scarcity of proper food and drinking water, primary education, basic health amenities and fifth —social harmony. I had planned in my mind that we would work in 350 backward districts of the country. In order to perform this task I had decided to quit the post of the president of Janata Party. But I could not do this. After the Yatra I became trapped in the politics of opposition. That was my mistake.” In the book Rahabari Ke Sawal, edited by Rambahadur Rai, he expressed regret for joining the electoral politics and, in the process, forsaking the common people and the youth who had joined him during the Yatra.

Despite this realization, to the very end, Chandra Shekhar could not gather the courage to remedy this error of judgment and rectify his mistake. This was unfortunate, particularly because concrete efforts in this direction had already been initiated at several grass root levels. The decision to turn away from mainstream politics that had increasingly begun to toe the line of globalization and seek alternative modes of seeking solutions to political dead ends had already been pushed forward by another veteran of the socialist movement, Kishan Patnaik along with several young and senior socialist leaders.

If Chandra Shekhar, like Patnaik, had broken away from the yoke of mainstream politics, the way he had done during his Bharat Yatra and opted for alternative politics, it would have been very difficult for neo-imperialism to sink in its teeth so irremediably in the country’s economy. Many committed socialist workers find it curious and also a pity that while Chandra Shekhar had dialogues with and the cooperation of intellectuals and leaders like Deoras and Nanaji Deshmukh from other ideological groups, there was none of the socialist leaders who were involved solely in this direction. Whatever may have been the reasons, had there been a closer association between them, a stronger resistance to globalization would have certainly emerged. Leaders, commentators and the media might well have ignored his role as the one who opposed globalization. But history will always present him as an uncompromising political figure who will continue to inspire generations to come.