(Samaj Weekly)

– Vidya Bhushan Rawat

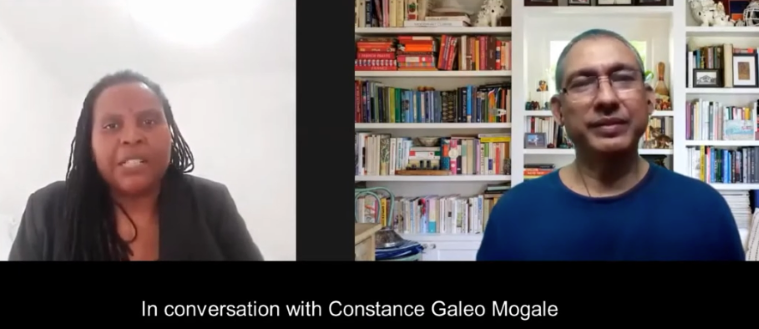

Constance Galeo Mogale explains Racism, Land Reforms and why she passionately speaks for Food Sovereignty in South Africa

Constance Galeo Mogale is an experienced South African land activist who has played leading roles in several campaigns and initiatives. She led a grassroots movement called the Land Access Movement of South Africa (LAMOSA), A federation of communities claiming land through Restitution, an organisation that challenged the Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act of 2015. She has a proven record in mobilisation, and have extensive experience on participatory research She currently coordinates the Alliance for Rural Democracy (ARD,) a loose network of organisations campaigning for land rights and livelihoods in South Africa. She is also holding a Post Graduate Diploma in economic Management Science in the University of Western Cape and currently a 2018 Cohort of Atlantic fellowship programme, a partnership of Nelson Mandela Foundation and Columbia University in the USA. She is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Economic Management Science. In a wide ranging conversation with Vidya Bhushan Rawat, Ms Mogale explained various issues of land rights, gender issues and racism in South Africa and why she feels so much about them.

She says that , “The need for radical social movements arises from the betrayal of promise by the current Government, which failed to transform the skewed patterns of land ownership and reversing the legacy of the History of Dispossession The bitter colonial history of dispossession in South Africa tells us that land was taken from as far as the 1800. in 1913 Africans were cordially allocated 7% percent of their country. 93 percent of it was handed to 349,837 colonial settlers. When this land was found inadequate for Africans the Tom lion Commission was appointed in 1916 and it was because of its findings that 20 years later, the colonial parliament passed the Native Trust Land Act 1936 which added 6 percent to the 7 percent allocated to Africans in 1913.This left the colonial settlers with 87 percent.

In 1950 the colonial parliament passed a law called Group Areas Act 1950 to remove those Africans who were too close to “European” land. This was to intensify colonial racism, which in 1948, colonial Prime Minister Daniel Malan named “apartheid” (race separation). When the situation did not change and the revolutionary movements in South Africa resorted to the armed struggle; the apartheid colonialist regime resorted to creating “tribal republics” for Africans where they would “rule themselves.” They were nine “republics” called “Homelands.” They were called Ciskei, Kwa-Ngwane, Lebowakgomo, Kwa-Ndebele, Venda, Kwa-Zulu, QwaQwa, Transkei, and Bophuthatswana.

But maybe the reconciliation argument from the moderates, ANC ruling party could be, let us talk the here and now as it its complicated to resolve issues of 100 centuries ago. we need to bite what we can chew and talk the land rights now! The South African government land reform programme was supposed to deal with this injustice and provide redress, they failed! Only about 9% of the land was redistributed in 26 years since 1994 Many South Africans are frustrated by this slow pace hence the call for radical transformation on land and economic assets.

Unfortunately, there is a very big generational gap and knowledge deficit between land activists since economic factors are dominating the narratives. The young activists are following the trends, ANC and other political movements has gave up its liberation agenda, they are now economist activists who are promoting agenda of accumulation and pushing up the bank balance. It is difficult for social movement to function without capital and funding. So, the state of social mobilisation is very weak and co-opted.

On the question of Women

There are various spaces created for women only organising, for example we have different movements having women’s leagues, young adults’ forums and so forth. These spaces assisted a lot in trying to outroot the silent voices of women from the male dominated spaces, however without strategic integration, it will always be ‘US and Them” We must also take into account that women are just not homogenous, they are part of communities from different classes, different positions of privilege, ethnicity, race and all. The question is whose voice is louder and why? To answer the question posed here correctly, perhaps we need to categorise these women spaces to be able to do justice in unpacking it.

Generally, women continue to play a vital role in the struggle for social justice in South Africa, yet their contribution is still unappreciated, and they are still marginalised. The reason is that most women themselves are still abiding by patriarchal systems and the social stereotypical defined gender roles. If you look at the contribution of women in all big movements, the churches, and the social groups, they are underestimated.

Their contribution is in terms of numbers, their double reproductive role and care work, yet their mindset and attitude are still one that is submissive to the masculine gender, to serve and to do the spadework. South Africa is often referred to as the “rainbow nation” to describe the country’s multicultural diversity, especially in the wake of apartheid. The World Bank classifies South Africa as an upper-middle-income economy, and a newly industrialized country. Its economy is the second-largest in Africa, and the 34th-largest in the world. In terms of purchasing power parity, South Africa has the seventh-highest per capita income in Africa. However, poverty and inequality remain widespread.

The Land Question in South Africa

Landless is increasing, the trend is moving towards prioritising commercial production as opposed to social housing and social production. This trend has made the South African government vulnerable during COVID19, and the social safety nets of the country are generally weak to cope during disasters. This question is almost a follow up of the first question in the history of land dispossession.

South Africa’s total land surface is 472,281 square miles. But from the early 1800 to 1969 through what the apartheid colonialist regime called Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act No. 46, nine “Bantu Republics,” established and allocated 68,264 square miles of South African territory. The remaining 404,017 square miles with all its mineral and agricultural wealth and other national resources remained under the control of the minority white population, many of whom still have the arrogance to claim that they did not take land from anyone. They found it “empty!” Oh! well, maybe they thought it was empty because Africans did not have boundaries, border gates, it as a free access to those who use it. We lost freedom of movement and were deprived of scarce natural resources.

I am an advocate of rural land, but landlessness in South Africa is more visible in peripheries of big cities and economic hub provinces such as Johannesburg, Durban, Capetown and Eastern Cape. Whereas I sometimes question the kind of reforms we are advocating for as South Africans, I am in full solidarity with the urban movements who continue to occupy land even if it means that they face the barrel of the gun from the SAPS, the Anti–Land Invasion Unit, the JMPD, the Red Ants and the so called Law Enforcement in Johannesburg, Durban, East London and Cape Town. These poor law-abiding citizens are criminalised for losing patience with the collapsing property redistribution system. They are impoverished people who continue to face evictions throughout the country.

The rural areas are so impoverished that people want to be closer to the cities so that they can improve their lives. When they occupy unoccupied land is because they seek to survive and to thrive, but most of the time they do not yield the expected results. We have seen now during COVID-19 era how black people who occupied land in search of economic opportunities struggled to put food on their tables.

Is the government redistributing land to the people or not? If yes, how much land has been allotted to people particularly those of African origin.

Government has not done well in Redistributing land to the black dispossessed people of our country. Statistics shows that ever since 1994, only 9% of the land was distributed, owing to the failed promise of 1994 ANC Manifesto, which promised to distribute 30% of the total surface area in 5 years, that was in 1999. The goal post shifted from 1999 to 2014 and still the Government failed, by 2014 only 4% of the land was redistributed, and mostly for urban housing and urban claims which was mostly done through cash compensation rather than land. This is because of an ever-changing policy framework which regressed from Reconstruction and Development Programme in 1994 to Growth, Economy and Redistribution Framework (GEAR) which was hailed by many economists but was highly criticized by labour movements and many CSO’s. GEAR was the Government five-year plan that focused on privatization and the removal of exchange controls, which was never evaluated to date.

This affected land reform policies where we saw the changes of Redistribution Policy from Settlement and Acquisition grants to Land for Redistribution and Agricultural policy which favoured commercial farming and monopolising of the industry. South African Government has no law which regulates redistribution and guiding officials on who is supposed to benefit, what land for what purposes. The policies proposed e.g. Proactive Land Acquisition Strategy (PLAS) has turned South African beneficiaries into tenants, and LRAD has left many farmers indebted as grants were badly managed by Land Bank, one of State-owned enterprises.

Is there any law that prohibits people from amassing huge agricultural land, basically, the upper limit of having land. Like in India we have Land Ceiling laws which make land above a certain limit as unlawful but then there are lots of gaps as people can acquire huge lands in the name of religious places, institutions as well as cow shelters.

We need a Land Redistribution Act and Subdivision of Agricultural Land Act in South Africa.

There is nothing in place for now. Policies such as land ceiling, Limitation of foreign ownership of land in South Africa, have since been proposed in 2005 Land Summit Resolution, but have never been implemented. In Redistribution, every new minister coming to power has proposed their own new policies such as Proactive Land Acquisition Strategy and LRAD, but these are not monitored and no one can hold the Government accountable, since these are just voluntary policies and not proclaimed acts of the law.

There are 2 progressive reports that was developed through appointment of High Panel On High Level Panel On The Assessment Of Key Legislation And The Acceleration Of Fundamental Change, led by the former Deputy President, Kgalema Motlanthe and the second one was appointed by the current President himself, Hon President Ramaphosa called Key Advisory Panel o land Reform which also presented very progressive recommendations, but all those progressive reports are overshadowed by the debate to expropriate land without compensation.

How did you come in the Land Rights movement and when?

I was born in the farming families who were dispossessed of their land and forcefully removed to further arid areas where farming life was impossible. Every evening, there was a group of male elders who used to gather in our house to discuss their fate, and to plan on how to react to the current challenges of livelihoods. My Grandmother was compensated with a 21 hector smallholding but she was never allowed to occupy it, she settled in the village which was 30 km’s away where everyone was given 450sqm yard, so it meant that the livestock would be taken care of by family uncles and she had no access or control to that wealth.

In 1991, when I was completing my matric in Ramatlabama, I saw on television that the same group of strategists who always met at my Grandma’s house were occupying the land forcefully in Ventersdorp. This activism was inspired by the release of Tata Nelson Mandela in prison. Many other dispossessed communities around the country were also going back to their land forcefully, supported by organisations such as Black Sash, The South African Council of Churches, Legal Resources Centre etc. It was in those years that the Bantustan system was also attacked, and that inspired me to join those elders in their movement building. Shortly after that, a movement called the Land Access Movement of South Africa was born, and when they formalised in 1999, I was recruited as the National Organiser in 1999.

What was your childhood about. Your parents and village?

My childhood life was that of a rural girl. I know all the chores of being a rural young girl who must walk more than 5 km to fetch water and wood. In the compensatory land of Vrischgewaagd where water was non-existence, as girls we used to take laundry and take a journey to the nearest stream to wash clothes. We used to collect dry cow dung to make fire, although at that time cows were kept far away from the village, and owners would deny us access, but we were fortunate because my grandmother owned livestock.

My parents were both migrant workers in Johannesburg, my mother was a live-in domestic worker and my father was a petrol attendant. My father was originally from Lichtenburg, Botshabelo near Lichtenburg and my mother were from Goedgevonden near Ventersdorp. Their communities where forcefully removed, my father’s family was removed to Ramatlabama near Botswana and my mother’s family was removed to Vrischgewaagd near Delareyville where I was schooled until Grade 8and went to my father’s village to do my High School in Batloung.

I am very thankful for my childhood because I became a resilient young mother, who acquired survival strategies from both of my grandmothers. I know how to use little water and recycle it for other uses, I save my own seed for next planting, I preserve summer vegetables for winter consumption, I know how to manage livestock and have inherited livestock from my grandmother, I bring valuable advice to other subsistence farmers but I also gained a lot of knowledge from framer activist in other parts of the world.

Did you ever face racism? If yes, what was it about?

Everyday, in one way or another. I never wanted to narrate many stories because they open healed wounds, but also make me seem like I am looking for pity. Landlessness is equal to racism, the fact that it is only black people who are still denied their rights to land is racism. But perhaps that could be too general. It is not only racism, but class segregation and gender. I felt it more when I moved to Johannesburg, working as a head of the black owned movement called Land Access Movement of South Africa. Discrimination as black commuting girl: It was difficult for me as a rural undergraduate girl and having to prove my ability to manage and run the movement effectively as a black woman with a rural background and having no social class or standard in the city. I stayed in my aunt’s house in Soweto commuting to work by taxis, having to wait in the queue as early as 5.30 to be able to reach my office at 8 am. The taxis in Soweto operate from 4.30 am to 8 pm and after hours, you need a private shuttle to go home. It meant that I could not attend most meetings outside the vicinity of the city centre and could not participate in important decision-making spaces attended by other fellow white directors, yet I sat in the board of Directors of the former National Land Committee who were 80% white and I was the only black South African woman in the board.

The salary survey showed that I was less-paid Director, which to me was okay because I knew that I am in a deficit of Educational qualifications. With the salary I received I had to build a home for my parents and my siblings, who acquired a site in Dobsonville, and we lived in a shack at that time. I also happened to have 3 children whose father abandoned me, so after the building of my Parents house, I had to prioritise their education and take them to school, that meant surplus money that I could have saved for my own education went to their education. I managed to build my own house, and now I graduated in 2018 and have applied to do my master’s degree.

I believe that white privilege must deal with it in the same way that I had to deal with my circumstances of rurality and blackness. I am not complaining, rather I am counting myself one of the few fortunate ones, because some are still trapped in these Poverty circles, caused by various reasons and without some saints giving them a break through it means their coming generations will still find themselves in the same situation. When you get a decent income, but you have to support your siblings, you have to build a home, you have to carry the cost for funerals and orphans in your family etc, when are you getting a break through?

Has racism finished from South Africa or it still exists?

Unfortunately, yes! Racism still exists in South Africa, as it is so visible that it is in our faces and we must gather courage to speak out about it, because keeping silent means we perpetuate it and we lose our own voices. Policies still favours the rich, there are clear cracks of divide between white and blacks in terms of redistribution of wealth and capital, by both the state and the financial sector. The income disparities between black and white and the resilience in times of disasters by white led companies versus black led companies.

It is a fact that white people inherited generational wealth of capital and experience, therefore they are mostly debt resilient, but also if you look at the financial systems such as insurance companies, banks and the mortgage companies have always treated black people with contempt and trapping them into debt by making them pay premiums that they can never sustain.

Black farmworkers and domestic workers who work in private homes are enduring racism attacks and falsely accused every day. It is so bad in a way that the media has chosen to report these cases in isolation and selectively, as if black lives do not matter.

We all talk a lot about the land reforms but when Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe wanted to legally acquire land from the powerful white farmers, there was a hue and cry. I am sure there are similar situations in your country. Is there a resistance from the Western governments and organisations about radical land reforms in your country? I mean how long can we have this unequal order where some people have thousands of hectares of land while many others do not even have space for their livelihood.

Regarding the Zimbabwe Fast Track Land Reform, the outcry was coming from the exempted blacks who signed up for western methods of politics, as South African we still regard Mugabe as the best African leader ever, especially when coming to decisiveness and clarity on matters of land reform and Zimbabwe systems of education. Robert Mugabe, like U Tata Nelson Mandela was never a saint, but for lack of better role models they were the best.

Our current Governments are continuing to reverse the gains made on land reform and transformation, they could not distribute the land and now they have discovered mineral wealth in the over-populated communal land. They are making laws that will empower the apartheid appointed traditional leaders to make decisions around mining on behalf of people, no Prior and Informed consent. In recent years, there has been an unexpected onslaught against the land rights of rural people in South Africa. This threat comes from new government policies and laws that set the apartheid-era homelands or Bantustans apart from the rest of South Africa as zones of chiefly sovereignty and undermine the citizenship rights of the people living within them. Urgent interventions are necessary to stave off imminent and irreversible dispossession.

New laws and policies betray this promise, however, and further dispossess the very people who bore the brunt of the Land Acts and the brutal forced removals that culminated in the consolidation of the Bantustans. These laws and policies seek to separate the former Bantustans from the rest of South Africa as zones of autocratic chiefly power, in the process transferring ownership and control of land that ordinary people have inherited over generations to traditional leaders. President Zuma sees traditional leaders as important strategic partners who can deliver the rural vote at a time when support for the ANC is declining in the major cities, including Johannesburg.

Driving these laws and policies is the irony that some of the former Bantustans, once assumed to be the least valuable land, have been found to hold massive reserves of valuable minerals – platinum in North West and Limpopo, coal and iron in Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal and titanium along the Wild Coast of the Eastern Cape. The poorest South Africans live on some of the richest land, but for many this has proved to be a curse, rather than an opportunity.

The primary beneficiaries of South Africa’s new mining rush are not the people, but mining companies and politically connected elites, including traditional leaders. Recent law specifies that the state will grant mining rights only to companies with black economic empowerment partners. It is an open secret that officials often dictate who such partners should be. The scale and spread of mining investments by senior politicians and their close associates is no secret, and we continue to mobilise rural citizens to defend their land rights against these big giants.

How powerful are the religious groups in your country in the social movements. Is it good or bad? Sometimes, people feel that radical religious groups dilute the revolutionary spirit. What is there in your country?

Religious groups are still powerful in terms of numbers and influence. However, because most of the formally recognised churches that survived apartheid have been intellectually weak because the South African Council of churches is in alliance with elite unions such as COSATU and Government. We have seen stalwarts joining Government as Ministers, and these churches have enjoyed foreign funding at the favour of Governments. That paralysed their objective voice, but we have also experienced activist voices of stalwarts like Bishop Tutu, Barbara Hogan, Moletji Mbeki, and others.

We have heard you speaking so powerfully about Food sovereignty issues which were resisted at the Global Land Forum in Antigua by the international organisations. Why are you so passionate about Food Sovereignty and what is its difference with Food security?

So, the terminology and language used in big forums and especially where the world bank and IMF are participating shapes narratives in a way that defeats the indigenous ways of survival. To me Sovereignty means autonomy but interdependence of systems to survive without depending on a system that is designed to exclude the majority from their own production spaces.

The fundamental difference between Food Security and Food Sovereignty is that Food Security seeks to address the issue of food and hunger through the current dominant food regime, whereas Food Sovereignty challenges this paradigm and seeks to build alternatives, and attempts to address the root causes through a bottom-up approach.

Food Security could mean adequate, but does not address access and control, it monopolises access, through big supermarket led redistribution where those who have no income stands to lose. whereas food sovereignty means people are in control and can choose what they eat, their access depends on the amount of work and labour they provide. This is very powerful.

In conclusion, the most worrying factor is the minimal role played by the state, which should be a referee in the fight between big companies and the communities. They are fence sitting and thus giving institutions such as banks and bank companies a leeway to abuse power and repossess land if people struggle to pay. On the other hand, small scale farmers inability to manage their group dynamics contribute to their inability to use the land productively. There is no Institutional support on Governance and Management for groups, Lack of farming skills on the part of black farmers, Inability of the poor people to raise “own contribution ” money and thus lost the opportunity to benefit from the programme.