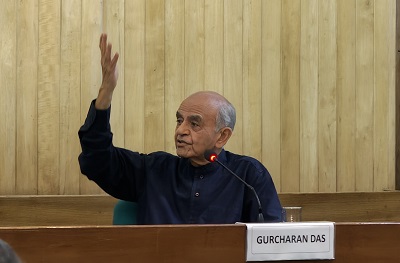

New Delhi, (Samajweekly) Top corporate executive of the yesteryear and now an acclaimed author and public intellectual, Gurcharan Das, has laid out a feast for thought in ‘The Dilemma Of An Indian Liberal’ (Speaking Tiger), which was formally released here on Wednesday evening.

Known for consistently advocating liberal values, Das began by explaining etymologically what the word ‘liberal’ stands for.

He noted that out of the three-fold guiding principle of the French revolution — Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity — fraternity seems to have been forgotten today, even as the noise around liberty gets louder.

Making no bones about the journey of his ‘evolved’ socialist values, he said that “the liberal is always suspicious” of those who wield religious, military, economic, or political power.

Talking about his liberal “heroes” — Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru — and pointing out that the country’s first prime minister introduced the word ‘socialism’ in our national vocabulary, turning the author and his family into socialists, he shared an anecdote from the time when he worked for the US multinational, Procter & Gamble, that produced Vicks Vaporub.

There was a year of the flu and “we produced a hell of a lot of Vicks Veporub”. But in those days of the Licence Raj, the companies produced way more than they were permitted to. As a result, far from celebrating what they thought was a great job done during an epidemic, they had to deal with the government’s summons accusing them of breaking the law.

Informed of a possible three-year jail sentence for breaking the law (by overproducing for consumers in need), his interaction with the bureaucrat led Das to change his mind and he became a libertarian from a classical liberal. And he joined the Swatantra Party.

Recalling his “moment of conversion”, Das emphasised the fundamental importance of a market economy. “Nehru was a creature of his times and all were socialists then, but by the time of Indira Gandhi, the world saw the rise of Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, that had already become Asian Tigers or were in the process of becoming that,” he said.

Das pointed out that they became a middle-class country from a poor country on the basis of labour-intensive manufacture; and by the time Indira Gandhi could see that there was an alternate path, the world, which admired Nehru and India for safeguarding liberal democracy, began to regard the country’s experiments with a socialist mixed economy as being pathetic.

The cardinal error was that although Nehru wanted compassionate socialism, the bureaucracy toppled it with Licence Raj. India achieved political freedom in 1947, but it was in 1991 that India got its economic freedom, emphasised Das.

Recounting another story about the ‘steel frame’ of the nation, Das mentioned an unsung hero, Amar Nath Varma, who was Principal Secretary to Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, who held a meeting every Thursday. It was called the ‘Thursday Committee’. The secretaries of all economic ministries attended the committee meetings and one new reform was discussed every week.

The meeting’s minutes were discussed in the subsequent Cabinet meeting and press notes were released that evening. And in the weekend edition of popular business dailies, “It was Diwali.”

The Congress government is believed to have ushered in Liberalisation in 1991, yet it fell foul of reforms in the long run. “The mistake was that none of the reformers sold the reforms to the public,” Das said.

Quoting examples of Deng Xiaoping, who spoke every day about the market, and Margaret Thatcher, who said she spent 20 per cent of her time reforming and 80 per cent of her time selling reforms, the author said: “We were doing reforms ‘chupkey chupkey’ (furtively).”

And none of the future reformers, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Manmohan Singh and “even Modi, none of the reformers have taken the trouble to sell the reforms, which means that people still believe that reforms make the rich richer and the poor poorer. They still believe there is no difference between being pro-market and pro-business.”

Noting that manufacturing represents less than 17 per cent of the GDP when it should be double of that, and the exports of any manufactured commodity are less than 2 per cent of the total production, Das said: “If we increase that by 2-3 per cent, we will have an industrial revolution.”

So, what went wrong? We did not create that industrial revolution, “but we are in a far better position right now to create it because our infrastructure is far better that it was in 1991”.

In 2014, when the author was fed up because of the absence of real reform, what attracted him most to the change promised by Narendra Modi was his slogan of ‘Minimum government, maximum governance’.

Landmark events such as demonetisation and its flawed execution began to make Das lose faith in Prime Minister Modi, but he’s now convinced that it is only the Modi government that can truly fast forward necessary reforms.